Heat

What is thermal energy?

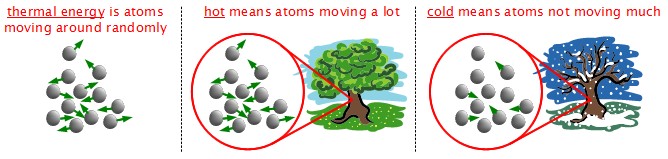

Everything is made up of very tiny things called atoms. Thermal energy is atoms vibrating, moving around seemingly at random. When we say something is hot, we are really saying "its atoms are moving around a lot!" or it has a lot of thermal energy. When we say somthing is cold, we are really saying "its atoms are not moving much." or it doesn't have much thermal energy.

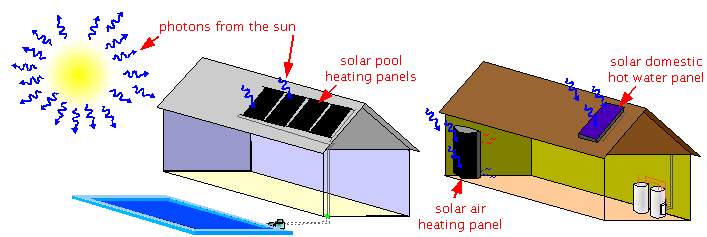

How does the sun heat things?

Photons come from the sun. Think of photons as little bundles of energy. When they encounter something here on Earth, such as a solar water heating panel, they give up their energy to the atoms in that panel. You could think of it as they've bumped into the atoms, making the atoms move. They've increased the amount of random motion of the atoms which from what we've just said above means we've just increased the amount of thermal energy, the panels have become hotter.

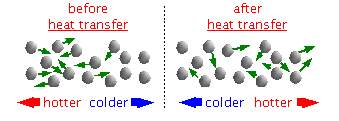

What is heat - heat transfer?

Atoms that are moving "bump" into atoms that are not moving, making those atoms move too. The atoms that did the bumping will have lost some of their energy so they will move less (they've gotten colder). The atoms that got bumped into will have gained some energy and will now move more (they've gotten hotter.) A popular expression that sums it up is "hot goes to cold", heat travels to cooler areas, making them hotter. Of course the area that was previously hot gets a little cooler in exchange.

Heat then is the energy that's transfered from one area to another area, changing amount of thermal energy in the two areas.

Learn more about heat transfer/loss, including how it relates to houses, solar air heating, buried heating tanks, ... along with a calculator, on the main heat transfer page.

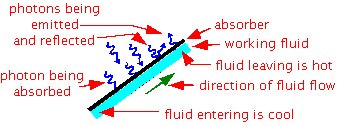

The heat absorber

Some material is needed that is good at absorbing the photon's energy and turning it into thernal energy. This is called the absorber. It is usually a dark colored sheet or tube. It becomes hot and transfers its heat to the working fluid that's behind or inside it: propylene glycol, water or air.

As long as the absorber is a dark color then it will absorb the sun's energy and turn it into thermal energy. The measure of how much it absorbs is called its absorptivity. So you want high absorptivity. If you don't take away the thermal energy from the absorber fast enough, then it will heat up. If it gets hot enough, it will begin reradiating the energy back out again. The measure of this effect is called its emissivity. So a high absorptivity and a low emissivity is best, but if the thermal energy is being taken from the absorber by your flowing air then it will not get hot enough for emissivity to matter much.

For homemade solar air heaters people usually use flat black paint. A good choice for this that is available to the average person and budget is the flat black paint for painting barbeques and radiators since it can handle the thermal energy without getting damaged and can be found in a spray can at your local hardware store. Its absorptivity can be as high as 94%1

Manufactured solar air heaters typically use a more expensive and hard to do coating but one that has high absorpivity and low emissivity (absorbs plenty and reradiates back little.) An example of this is black chrome, part of the process of which includes electroplating (a more difficult process than simply painting.) Its absorptivity ranges from .92 to .97 and its emissivity ranges from .8 to .252.

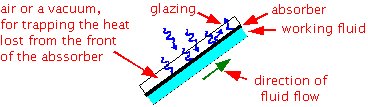

Keeping the thermal energy - glazing and insulation

The thermal energy from the absorber gets transfered to the working fluid because the working fluid is in contact with the back of the absorber. But what about the front of the absorber, the side facing the sun? Thermal energy can be lost to the outside air there. To trap most of this energy we put a sheet of clear glass or plastic.

This sheet is called glazing. The most often used type is tempered glass because it allows most of the photons to pass through it and if it breaks, it breaks into many small pieces rather than big sharp ones.

The area between the absorber and the glazing can also be emptied of anything, i.e. a vacuum. Since there is nothing (well, almost nothing) in the vacuum, there is nothing for the absorber to transfer the heat to so the absorber doesn't lose any that way.

Another step to take is to enclose all the sides and the back of the whole thing with insulation. Insulation, similarly to a vacuum, is poor at absorbing and transfering heat.

Learn more about insulation on the main insulation page.

For more about heat energy...

References:

1. STT 100: Solar Domestic Hot Water Installation - Fundamentals.

Canadian Solar Industries Association,

Version 1.4, October 2005, pg. 15.

2. Ibid, pg. 27.